Building Riff Backgrounds

Download a PDF of this post here.

A riff is a short, repeated phrase that can be used as a primary melody or as background accompaniment of a melody or improvised solo. Riff backgrounds are used to support the melody or an improvising soloist while developing the melodic materials of the composition, building energy, and defining the overall form. Riff backgrounds use a straightforward development strategy that increases tension by layering riffs on top of one another. A classic example of this layering follows a pattern where a new riff is added every time the form turns over, every two, four, or eight bars, or any other logical duration where the primary riff can be heard in a repeating cycle. The progression of energy in a solo with riff backgrounds tends to be a straight line from where the riffs begin to the climax at the end of the solo.

Why write solo backgrounds at all?

Bob Brookmeyer described solo backgrounds as a means of, “keeping your hands on the soloist.” Backgrounds allow the writer to ensure the soloist moves everything along according to the writer’s plan, not the soloist’s whim. Backgrounds are a way of influencing the soloist and ensuring that they:

Play their solo based on the musical materials of the tune.

Develop their solo in a way that leads logically to the next section.

Create a climax when the writer wants at a scale that suites the overall climax structure of the whole.

Creating energy behind a soloist

Repetition

Repetition of any riff creates a feeling of musical expectation. By repeating something you’re drawing the listener’s attention to it. Once a riff is clearly in the listener’s ear, new riffs that are layered on top of the primary riff are more immediately understood and begin to create their own musical expectations. The greater the listener’s sense of expectation is the more tension is created.

Density

Density can be either harmonic, melodic, or rhythmic. As ensemble density increases the soloist must alter their solo in order to be heard and to match the vibe of the given moment. Increasing ensemble density pushes the music forward and goads the soloist into fulfilling the solo section’s formal requirements.

Harmonic density can be the number of voices used to harmonize a given line (octaves, 6ths, 4wc, clusters, etc.). Thicker voicings create a fuller, more energetic sound.

Melodic density is the number of individual lines being heard in counterpoint.

Rhythmic density is the amount of syncopation, the interlocking of rhythms between orchestral sections, or note velocity.

Registration

Changing the registration of a riff up an octave amplifies the amount of tension and excitement generated by it sonically.

Dynamics

By increasing the volume of a riff the soloist will have to increase their volume, as well as register if they want to be heard clearly. This allows the writer to influence what the improvised solo sounds like and how and when it climaxes.

Pre-compositional Process

A little pre-compositional planning will help you write backgrounds that flow logically into the next section. If you know where you’re headed you’re more likely to write in a direct, effective way.

Determine the length of your riffs.

Consider of solo form, overall length of the improvised section within the whole of the piece, desired complexity of counterpoint created by the layered riffs, etc.

Is the primary riff the whole form of a blues? Is it two, four, or eight bars? The type of tune you’re arranging will determine what is feasible. Tunes with more open harmonic sections lend themselves well to riff backgrounds. Similarly, blues is an obvious choice because of the history of using riff melodies based on blues scales.

The subsequent riffs are often progressively shorter than the primary riff. Shorter cycles build energy faster than longer cycles. An example of how you might build energy: riff-A is eight bars, riff-B is four bars, and riff-C is two bars.

2. Decide the number of layers you want the backgrounds to contain.

The standard big band riff background on a blues is three layers, one for each orchestral body (saxes, trumpets, and trombones). More can also be effective if you blend the orchestral sections.

3. Decide the number of repetitions.

Based on the number of layers you’re planning on, how many repetitions of the riff backgrounds are needed to create the climax you’re looking for?

For example, if we take the 8, 4, 2 bar riff cycle from above we will hear the eight bar riff-A three times. Riff-B will begin at the beginning of the second presentation of riff-A and will be heard four times in total (two times for every eight bars of riff-A). Riff-C will begin at the beginning of the third presentation of riff-A and will be heard four times in total (four times for every eight bar riff-A).

4. Decide orchestration tools

What tools will you use to create energy behind the soloist? What will the balance be between repetition, registration, dynamics, and density?

Writing the Rriff

Determine the chord scale possibilities.

Consider what tension substitutions you’re interested in using when choosing your chord scale.

Find all common tones between the chord scales and use those notes as a basis to create your riff.

2. Write riff-A

Look at the melody of the tune. Determine what intervalic content will both reflect the melody, be easily digestible as a riff, and connected to the aesthetic “vibe” of the rest of the tune.

Leave ample rhythmic space for the other riffs to nest inside of.

Compose the end of the riff in a way that logically leads back to the beginning.

3. Write riff-B

Compose this riff as an extension of riff-A using the same intervalic materiel and aesthetic considerations.

Try to nest these two riffs together in a way that creates a coherent single line between them while still leaving room for the third riff to nest into.

4. Write riff-C

The third riff can be constructed using the considerations from riff-B, or, it can be generated by using various parts of the first two riffs using the varying coupling technique.

Orchestrating the backgrounds

Lay out all of the melodies on your score.

Once you can see how all of the riffs fit together, sing through the backgrounds and imagine yourself improvising over the riffs. Tweak each riff as needed. Remember that less is often more.

2. Think about how you can build tension in each riff progressively by changing its orchestration.

Registration, dynamics, and harmonic density are the main tools to use at this point.

3. Start by orchestrating the busiest part of the backgrounds first. This is when riff-A, riff-B, and riff-C are happening simultaneously. Orchestrating in reverse order, back to front, guarantees you won’t write yourself into a corner.

4. Copy the last time through the backgrounds into the section before it and erase riff-C.

5. Copy the second time through the backgrounds into the first section and erase riff-B.

6. Tweak as needed and write the final climax where everything comes together at the end.

Examining riff backgrounds

I Be Serious ‘Bout Dem Blues, John Clayton, George Bohanon, trombone, Clayton Hamilton Jazz Orchestra

Riff-A

Repetition: Full chorus blues riff

Registration: Lower-middle register of trumpet

Dynamics: Mf

Chord scale: Blues scale

Riff-B

Repetition: 8-bar, two bar riffs with melodic development.

Chord scale: The melody is derived from the Blues scale

Interaction with Riff-A: Riff-B fits in the cracks of Riff-A. There are no simultaneous entrances between riff-A and riff-B.

Riff-C

Repetition: 8-bar, two bar riffs with melodic development.

Registration: Middle register trombones.

Chord scale: The melody is derived from the blues scale.

Interaction with Riff-A and Rif-B: Riff-C is derived from riff-B. Riff-C uses octave displacements of riff-B’s melody to create a distinct line.

Ending

All three riffs come together on the final melodic gesture of riff-A.

Orchestration of the backgrounds

First Chorus:

Riff-A

Density: Unison trumpets

Registration: Lower-middle register of trumpet

Dynamics: Mf

Riff-B Tacet

Riff-C Tacet

Second Chorus:

Riff-A

Exact repetition.

Riff-B

Density: Harmonized saxophones. A mix of harmonization techniques including 4wc, 5-note voicing, spreads, and unison. Liberal use of tension substitutions.

Registration: Full range of the sax section.

Dynamics: p-ff

Riff-C Tacet

Third Chorus:

Riff-A

Density: Harmonized Trumpets. A mix of harmonization techniques including 4wc, and unison. Liberal use of tension substitutions.

Registration: 8VA

Dynamics: F-FF

Riff-B

Exact repetition.

Riff-C

Repetition: two-bar riffs with melodic development.

Density: Unison and octaves

Registration: Middle to upper register

Dynamics: mf-f

Examining Riff Backgrounds

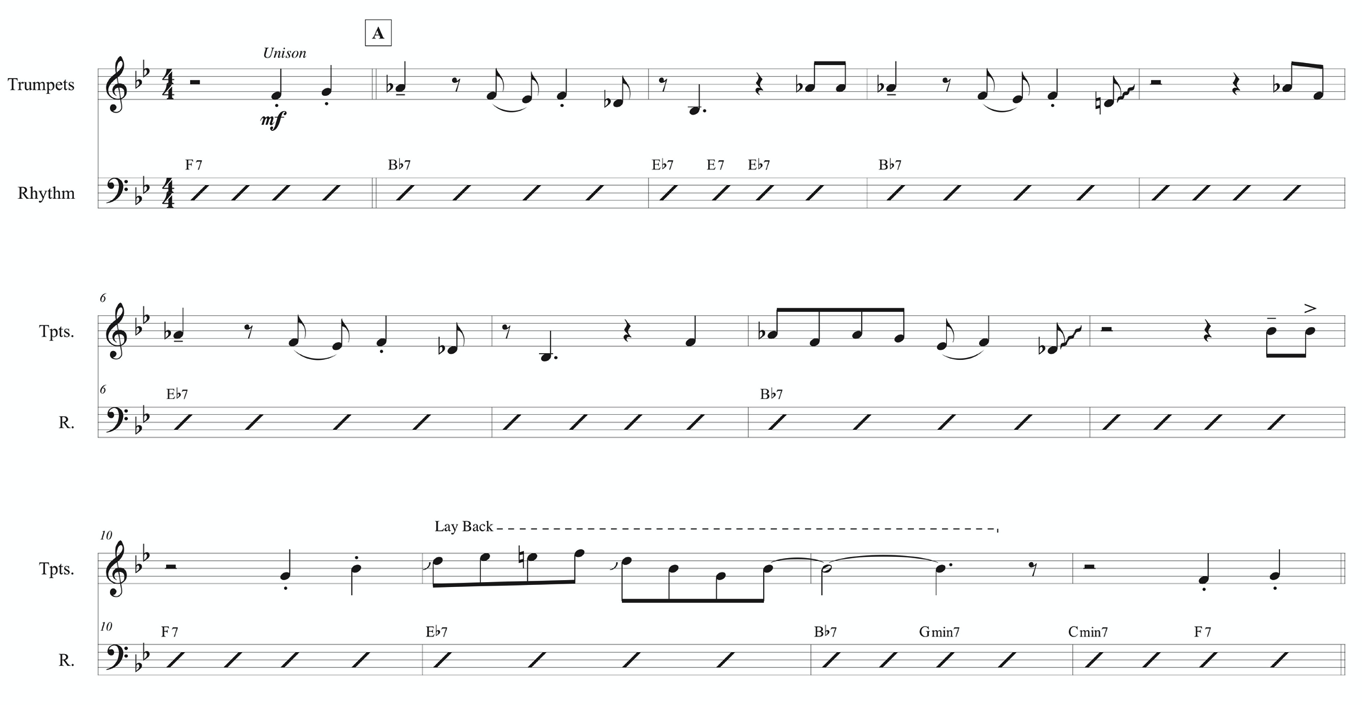

A Go Go, John Scofield, arranged, Nicholas Urie, tenor soloist, Michael Bladt, Aarhus Jazz Orchestra

The overall length of these backgrounds is 32-bars. Both riffs are based on the intervalic material of the tune and use a dorian chord scale. Riff-A is made up of two parts that nest inside one another, each lasting four bars. The riff-B is made up of a two bar riff that repasts twice in the space of riff-A. Riff B is a development of riff-A.

The development of energy is fueled by the number of repetitions and the gradually increasing volume, density, and expectation. The last four bars of the 32-bar background form incorporates the original bridge bass-line, and a closing sendoff that was developed from the first solo sendoff material.

Riff-A

Repetition: two part riff, four bars long. This riff repeats four times

Registration: Lower-middle register of trumpet, alto. Middle register trombone

Dynamics: Mp

Chord scale: Dorian

Orchestration: Intersectional orchestration using prime unison and octaves

Riff-B

Repetition: two bar riff with bass-line.

Chord scale: Dorian

Interaction with Riff-A: Riff-B fits in the cracks of Riff-A. Riff-B is an elaboration of the second part of Riff-A.

Dynamics: Mp, Mf, F.

Orchestration: Three part harmony in trumpets with doubled lead line. Bass trombone and baritone saxophone play unison bass-line.

Ending

Riffs come together with the tune’s melody to create a sendoff for the next soloist.

Chord scale: Dorian

Orchestration: Winds and upper brass are blended. Trombones play in octaves. Bass trombone and baritone say play a separate, interlocking line with the trombones.